Ethnographic Fieldwork

As an integral part of our project methodology, extensive fieldwork is conducted in the two sites of investigation: Río Blanco and Nimboyores. The following images are from a community tour of the aquifer in Río Blanco, located on the Caribbean coast. During these tours, collaborators identify locations where life above the surface and water under the surface intersect more intensely. Those intersections include infrastructural, bodily, more-than human points of encounter that enrich and/or make life harder. An example of that is the image below, taken after intense rains in 2023 toppled trees around the tanks that hold the water that is extracted from the aquifer before it is distributed to more than 2,300 households in the area.

Image: Andrea Ballestero.

The image below depicts a “Caseta” that houses a water pump, chlorination station, and security valves all of which work together to extract water from the aquifer and pump it towards users.

Image: Andrea Ballestero

Per national regulations, Community Aqueducts (ASADAs) have to secure their wells and restrict access to them. The sign in the image below announces to the public the presence of the wells and the prohibition to enter the property without formal authorization.

Image: Andrea Ballestero

The image below depicts a geological formation of the aquifer Río Blanco on the margins of the Río Quito. Different geological formations are crucial to understand when mapping aquifers as they can determine how water is distributed throughout the underground.

Image: Andrea Ballestero

Aerial Analysis

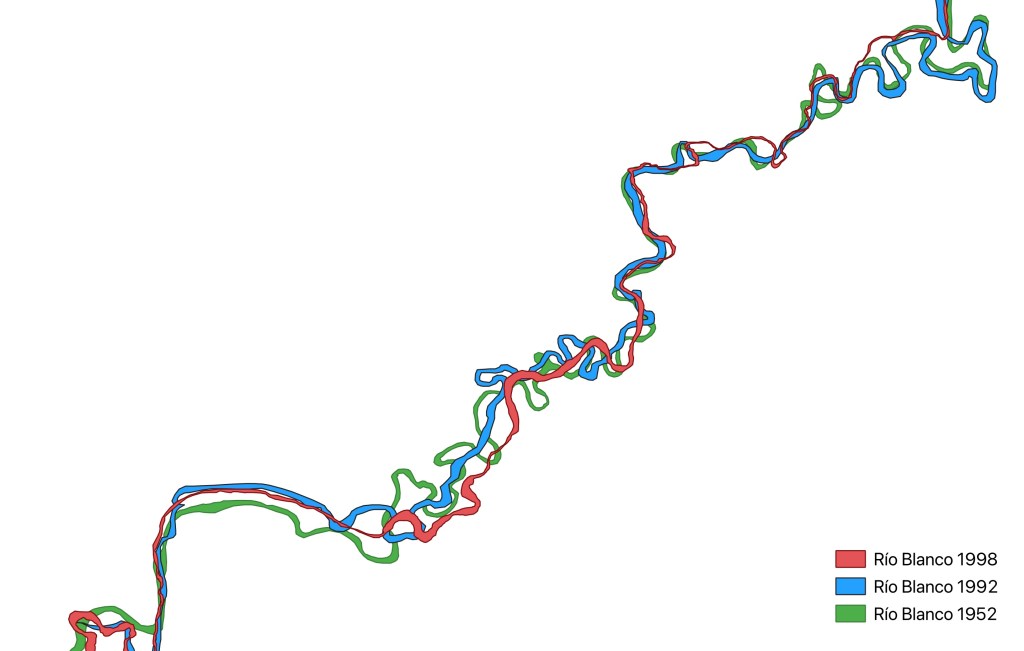

Project Working Image: Río Blanco: 1952 (Green), 1992 (Blue) and 1998 (Red).

Historically, aerial images have played a key role in prospecting and mapping groundwater systems. By looking at aerial images, hydrogeologists, for example, identify patterns, tones and textures on the ground. These patterns indicate features such as drainage systems that result from underground geological structures. These patterns also reveal sedimentary histories in the form of tone and texture which also provide clues of what lies under the ground. Once analyzed, aerial images are used to create maps of the probability that there is groundwater in a particular area. Therefore, the aerial perspective, despite its limitation in accessing the subsurface, has been foundational in shaping scientific imaginaries of the underground.

Aerial analysis in our project consists of interpreting historical aerial photographs and optical high-resolution satellite images over and around the two aquifer study sites. We collected aerial images from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the Costa Rican Geographical Institute. Over the Nimboyores aquifer, located near the Pacific coast, the earliest image we found is from 1943. In Río Blanco, located on the Caribbean coast, the first available image is from 1952. Once we received the photographs, we georeferenced the images using features such as roads and houses as stable anchors throughout the years.

In order to formulate the aerial analysis we ask: what visible features and processes on the surface shape imaginaries of the underground? Surface life includes a multitude of variables, infrastructure, urban development, agriculture, environmental disruption and change – all impact how we perceive and imagine groundwater. The sheer quantity of factors that can impact an aquifer is overwhelming, as a whole they exceed any visualization or study. This is precisely why visualizing and modeling aquifers can be so challenging. Deciding on which surface variables are factored into analysis is a crucial step tied not only to the objectives of a particular study but also to deeply held assumptions about social and natural worlds. What is considered to ‘matter’ on the surface, has a direct impact on how we visualize the subsurface. These decisions shape the parameters of a visual study, which in turn delimit its boundaries and potential edges.

This project relied on rivers as surface features that directly impact people’s understanding of aquifers–scientifically and culturally. The shape of the river, its width, curvature, and the types of sediment in the riverbed all provide clues about rock formations under the surface. The image above, for example, traces the Río Blanco in Limón across time, in 1952, 1992 and 1998. We can follow the river’s transformation by following its geomorphological change. From an aerial perspective, we can see the river’s path and form change, resulting in a kind of slow-moving undulation across time. Both underground geology, what lies beneath, and climate, what occurs on the surface, affect the river’s form. Tectonic activity is also inscribed in the river, and reading its transformations after a seismic event can teach us about plate movement. Rain patterns play a significant role in a river’s changing curvature in tropical – or wetter – environments, such as Río Blanco. Due to fluctuations in water volume, rivers move sediment consistently throughout the year, even if with different speeds and intensities, contributing to the transformation of overall form over time.

Perceptions of change vary at different temporal and spatial scales. From the aerial perspective, the changes are clear and easy to track. But from the ground, for example for those living close proximity to the river, changes can be perceived differently. To capture the “surface perspective”, we use this aerial analysis as a basis for discussion during interviews. The comparison between aerial and surface perspectives offer different understandings of change of the water bodies on the surface and their dynamic interconnection with aquifers.

Experimental Cartographies

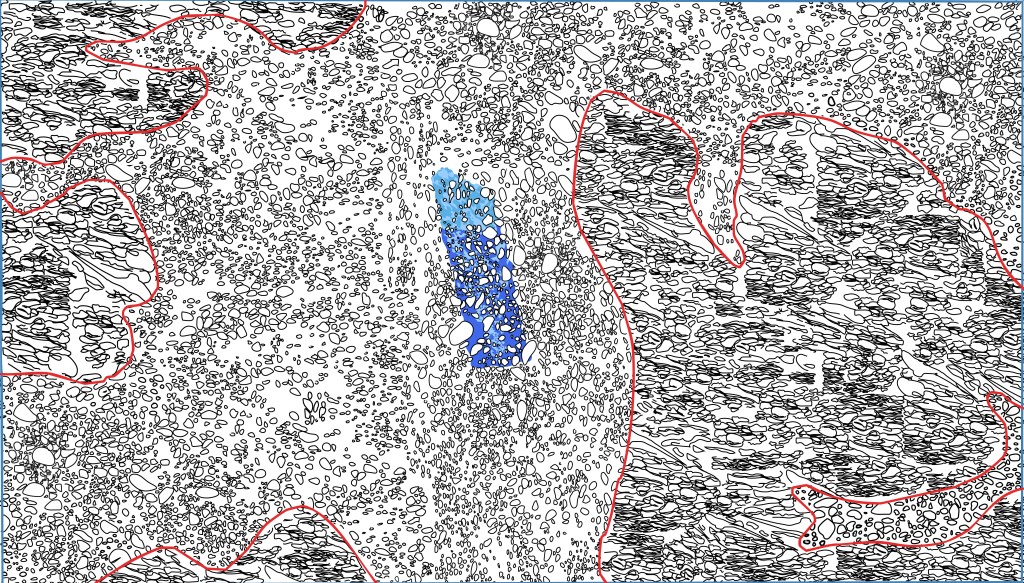

Project Working Image: Plumes of potential contamination embedded in the geological formations of Río Blanco.

The plume is an “elemental choreography”(Ballestero, 2020) key to understanding how liquids move in the subsurface through other liquids. The plume comes with a kind of warning, or associated danger. Plumes conjure catastrophic events and contaminated landscapes. Columns of smoke billowing in the sky during a chemical fire, an oil stain floating on the surface of the ocean, gas pouring into the atmosphere from a factory. The invisible plume also scares us; the unknown form and speed of a contamination plume moving through the subsurface, below our feet and under our homes. For these reasons the representation of plumes in their various forms must be treated with care. Signs of danger inscribed in the landscape might recall events that did not exist and imaginaries of apocalyptic futures that may not come to pass.

For our project, the plume is an invitation to experiment with dominant traditions of cartographic representation. The plume embodies the constant movement of water and substances in the underground. It is movement within movement. It emphasizes the non-static nature of the underground. Thinking through plumes moving in the subsurface requires thinking about the materiality of this invisible space. The material nature of the underground determines the shape and form of the plume, which is to say, its movement. Movement and material are hard to represent simultaneously in traditional cartographies or in cross sections of the underground. For example, the textures of the rock formations are abstracted for the cross-sectional view, often into a series of homogeneous layered patterns. Movement is stopped, or at best sometimes represented with arrows. It is visually rendered as a static condition rather than a dynamic process.

Our project experiments with drawing textures back into the subsurface in order to render movement sensible. Through visualizing texture, we might also visualize movement. The visualizing experiments are guiding by drawing techniques. Why drawing? For John Berger, whereas photographs stop time, drawings encompass time; drawings have the capability of encompassing temporalities not normally sensed by the human eye (Berger, 1972). We can draw beyond our own eye, which is precisely what visualizing the underground demands. A way of seeing which is beyond the eyes and beyond ourselves.

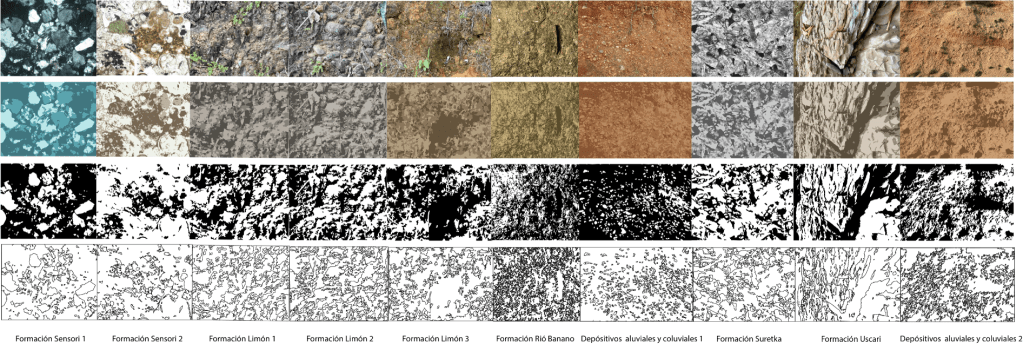

These drawings, made digitally and by hand, are layered on top of the rock formations in Río Blanco as described by geology. They are overlaid into the borders drawn by the Hydrogeological Study of Río Blanco commissioned by SENARA, Costa Rica’s underground water agency. These experiments are an invitation to think with materials as they relate to movement and form, and to consider how those materials mold how water travels through the ground beneath our feet.

News Archive Building

Since 2020, we have been building an archive of print news sources that focus on water, the subsurface, mining, oil, and aquifers. The objective is to gather public representations of the underground across time. These materials inform this project’s interest in the transformation of political discussions of the subsurface from mining, oil and gas to water matters. At the moment, we have a collection that includes more than three thousand sources starting from 1850 and coming from 34 publications. The database includes geolocation, titles, summaries, and keywords in Spanish and English. It also includes PDFs of each of the news articles and opinion pieces. This archive is meant to help our project and other researchers examine untold histories of how public attention moves up and down, inwards and outwards of the Earth. We are currently developing a an interface that will make these date accessible to the public.

News Sources Database: this screen-grab includes seven of the sixteen metadata columns for each entry.

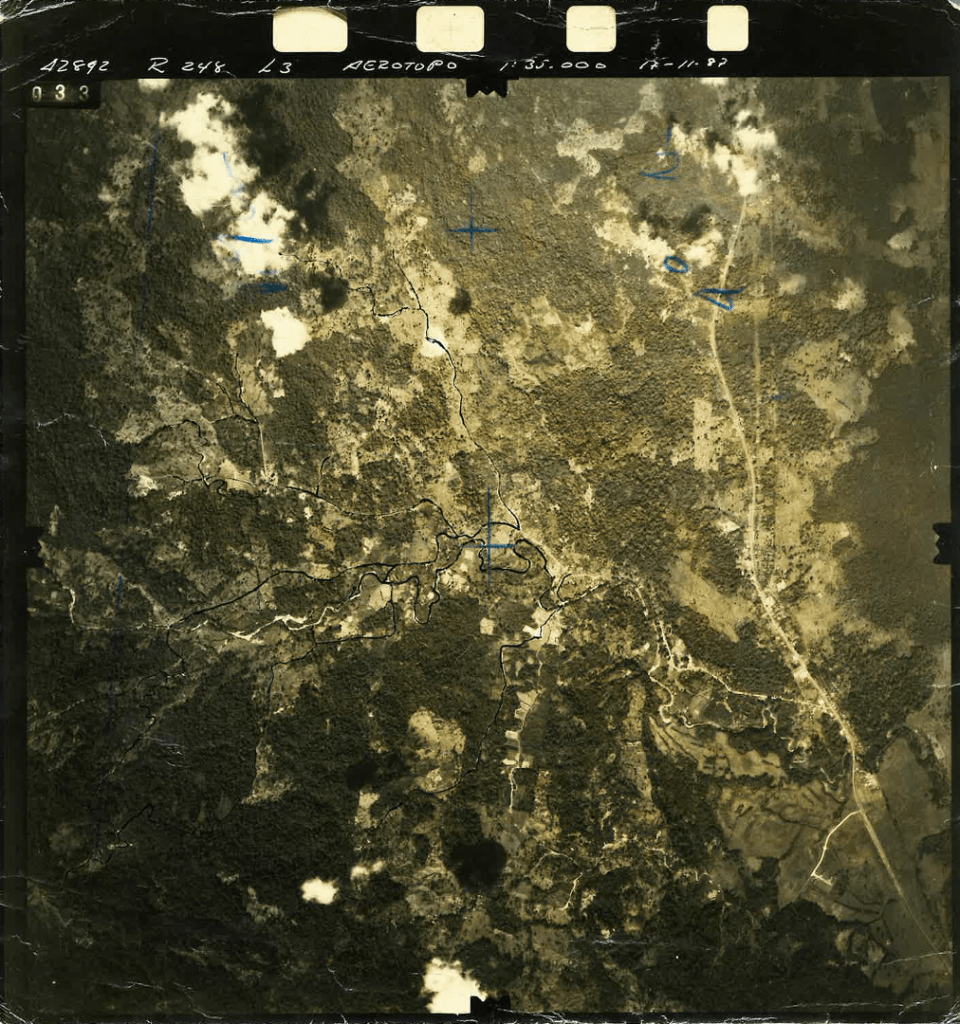

Aerial Photography of Limón Area (1952-2024)

The project also generated a collection of aerial images of Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast around the area of the Limón and Río Blanco. The early images are black and white photographs taken from airplanes. The latest images are produced using satellite data. The collection not only shows changes in the landscape, as seen from above, but are also aesthetic objects that enable different forms of experimentation. From the visibilities/invisibilities they suggest, to questions of scale, and further to geopolitical and political economic questions about their provenance. The images will be available in a cartographic platform, including annotations around a series of parameters that were drawn from the interviews as key concerns of our interlocutors.

Paper print of aerial photography facilitated by Río Blanco resident (photograph taken around 1980s), including annotations with blue and black ink done around the time of its production.